Gazing, Without Looking. Being Looked At, But Not Seen.

Project details

- Year

- 2023

- Programme

- Bachelor – Graphic Design

- Practices

- autonomous

- Minor

- Critical Studies

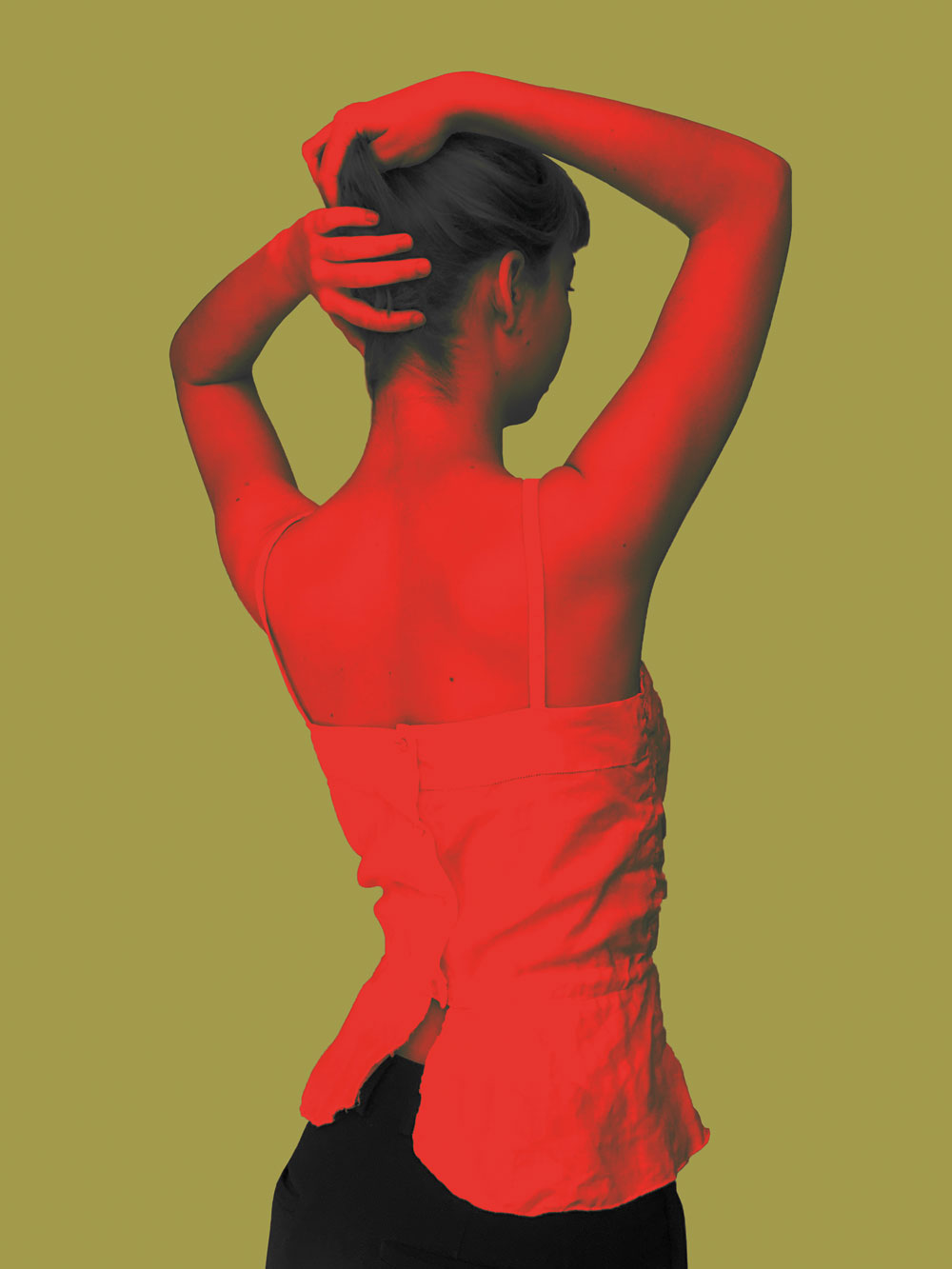

Gazing, Without Looking. Being Looked At, But Not Seen. is a visual investigation of the complexities of the so-called female gaze; how the male gaze is internalized, leading to the embodiment within women of both the surveyor and the surveyed, ultimately resulting in self-objectification. In the book, this process is visualized through personal experiences by means of texts, collages and self-portraits, referencing feminist theory and the cinematic technique of fragmentation.

Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? […] Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you’re unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

— Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride

Not that long ago, I was standing in my room, alone, in front of the mirror. However, I wasn’t looking at myself. I was looking at something, a thing. Something that was staring back at me. Something that looked like me, moved like me, but was not me. Not really. It had the same legs; the same arms; the same scar on the left palm of its hand from when it fell off its bike 15 years ago. It was staring back at me. Taking in my physical form just as I was doing to it. Obsessing over the size of its right thigh. The hair that was ever slightly too dark on its arms. The nail polish that was chipped and looked so uncared for. I saw the potential of the visual pleasure this thing could offer, but also all that was lacking for achieving such. It shocked me, looking at this thing staring back at me, the realization that all that I am so vocal about when it comes to others, or us as a collective, I could do to myself. I am the spectator; I am the spectacle. I am the surveyor; I am the surveyed. I don’t need a man. I can do my own objectification, all by myself; all to myself. That’s real female empowerment right there.

A term, heavily used in contemporary film studies (and visual culture), is the male gaze and its accompanied “counteract”, the female gaze. They are used to describe a presentation of the world —and especially women— seen through the perspective of either (binary) genders. However, both gazes lead to binary thinking and dualism, as perhaps any gaze does. It could be argued that to gaze implies more than to look at – it signifies a psychological relationship of power, in which the gazer is superior to the object of the gaze. [1]

From the moment we come out of the womb we are spectators, observers of the world around us. And every second we spend awake we are busy gazing, looking, seeing — whether that’s a conscious act or not. Therefore, it is of great importance to be critical of our own ways of seeing and to be aware of the underlying, internalized ideologies that shaped it. It is undeniable that most living in Europe have, to some degree, been conditioned by the male gaze. But to what extent do we internalize its beliefs? And how does that not only influence how we look at women, but also ourselves?

It is often normalized to look at our reflection and pick apart everything that is visually and aesthetically “lacking”. Turning the objectifying gaze inward. But this attitude didn’t appear out of thin air. It is thought behavior, as a direct result of patriarch. Thus, it shouldn’t be about gaining a new gaze, or giving the female gaze more authority. It should be about being critical of our existing ways of seeing: questioning them; deconstructing them. The male gaze itself is only a small consequence originating from a larger systematic problem. It therefore cannot be countered, or undone, by simply making it “female”, while remaining to uphold the current system. We need feminists critique because we need to understand how it is the world takes shape by restricting the forms in which we see… we need this critique now, if we are to learn how not to reproduce what we inherit. [2] And a crucial part of this critique is to also look inwards. To be critical of our own ways of seeing and how we, at times, are unconsciously controlled by the internalized ideologies of the male gaze. How it lives on within us. Recognizing the complexity of looking within systems of power, and about being a looking and consuming body within that [3]. Not only affecting how we see others, but also how we look at ourselves.

In the book, these concepts are explored through a personal approach. In what ways do I objectify myself? And what are the forces that influenced this way of thinking and seeing? Using the technique of fragmentation —cutting up the female form into little pieces of desirable skin [4]— the increased sense of self-surveillance is visualized. Combined with poetic texts, varying between personal and analytical, the objectification is simultaneously emphasized and refuted.

[1] Consuming Representation: A Visual Approach to Consumer Research, Jonathan Schroeder (1998)

[2] Making Feminist Points, Sara Ahmed (2013)

[3] Victoria Sin

[4] Agnes Verda

Read the thesis: The Weight of Seeing

See more work: www.bobbievanleeuwen.nl

Or get in touch: bobbievanleeuwen@gmail.com